The Role of Political Parties

Prepared remarks to First Year Political Science students at the University of Alberta later this morning

Good morning. My name is David Graham. I served as a Member of Parliament from 210 pounds to … 260 pounds. Politics is not really the vocation of the healthy.

Dr Wagner asked me to come speak with you today about the role of parties and so it is relevant to say here that I served as a Liberal Member of Parliament and have been a card-carrying Liberal most of my life.

But, what does that even mean?

There are a lot of people who will tell you that political parties are all the same.

I disagree wholeheartedly with that view, but I am not here to tell you why you should or shouldn’t support any particular party, but rather what the parties are there for in the first place through the lens of my own experience.

At a most fundamental level, political parties are meant to give people with common ideas or values a vehicle through which they can work together.

If I believe society should work a certain way, and so do you, then we can band together and make the “Certain Way” party, build up a team of people who agree with us, and present it in an election.

But if the people over there disagree and believe society should work in an entirely different way, they can work together to create and build a team around their ideas as the “Different Way” party.

When elections come up our team and their team will launch our campaigns and the public can decide whether they prefer the Certain Way or the Different Way approach to government.

That’s the theory, anyway.

In practice, what ends up happening is the Certain Way party says the Different Way party is full of shit. The Different Way party counters that the Certain way party are a bunch of lunatics. Pretty soon Godwin’s law is invoked and everyone’s calling each other Nazis and the system degenerates into the shouting match in which we find ourselves today.

Our parties stop being about ideas, at least during the election, people become disengaged and voter turnout drops, cynicism rises, and people start to think all politicians or parties are the same.

As I once read when I was quite young, if McDonalds marketing said, say, Wendy’s burgers are made of ground mice, and Wendy’s responded that McDonald's burgers are made of mealworms, what would happen? Pretty soon, nobody would be eating burgers any more.

That, in a nutshell, is the state of our political discourse today.

The trouble with this approach is that the ideas at the core of why parties exist in the first place are lost, and the whole exercise becomes a team sport. People vote for a party because their neighbours support it, their parents support it, their social circle supports it, and it’s not socially acceptable not to support that party.

Why the party exists, what it stands for, and what it hopes to accomplish are lost in the noise.

Most of you probably know Sir John A MacDonald as the first Prime Minister of Canada. But Canada existed before confederation in 1867, and prior to his arrival, we had a Parliament, a Prime Minister, and political parties.

The difference, when Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine worked with Robert Baldwin and the Reform Party through the 1840s when Upper and Lower Canada were forced to become the Province of Canada, the regions elected their MPs who then went on to express confidence in a leader who was then asked to be the first Prime Minister under the concept of responsible government by then governor general Lord Elgin.

You heard that right - MPs were elected without being bound to a party, associated loosely together, and selected from among their number a leader to lead the government. To lead a government, a Prime Minister actually had to maintain the confidence of the House; a majority was not a guarantee of anything.

Sir John A MacDonald was the first in a long line of Prime Ministers to work to centralize power around the Prime Minister and devalue the role of the peoples’ representatives. This has degenerated to the point that we now choose our party leader by self-selected “party members” giving control of government neither to the public through their elected members of Parliament, nor to the public at large.

Worse still, after the membership of a party have chosen their leader, the leader has virtually limitless power to take the party and its policies in whatever direction they want, with no real power by either the membership or, again, the elected representatives, to toss the leader and their team and ensure the party follows its stated values. In a conflict between a party’s stated policies, and the current ones of its leader, the leader’s policies are the ones applied.

This doesn’t have to be the case - Liz Truss’s 6-week reign as Prime Minister of England is a recent reminder that in other countries, even ones that share the same democratic foundations as our own, the political parties and their elected representatives actually retain significant power. Unlike in Canada, in the United Kingdom, majority governments regularly lose votes in the House of Commons.

Australia takes this even farther, with parties turfing their leaders so often that they even have an innocuous sounding term for it - a “leadership spill”.

By way of background, I got my first party membership before most of you were born. I grew up in rural Quebec, as an English-speaker in a profoundly French area. At home we spoke English, but everything around us was in French. In 1995, I turned 14 years old, the youngest age at which most political parties will sell you a membership.

That was also the year of the second referendum on Quebec separation. There were, from a partisan point of view, only two options for someone in Quebec who was politically engaged - the Bloc Quebecois if you did not believe in Canada, and the Liberals if you did.

So, for my 14th birthday, the only present I requested was a Liberal party membership.

The Conservatives had been reduced to just two seats in the election two years earlier, as much of their support had splintered off into the Reform Party and the Bloc Quebecois. The country was split into several disparate parties, as divided as I have ever seen it, rivaled only by the incredible divisions we have seen over the past years as a result of the covid 19 pandemic.

Fundamentally, I believed, as a teenager and to this day, that Canada is stronger united than we are divided, that the federation of Canada as a whole is stronger than the sum of its component provinces. That government fills a role in society and that citizens have a responsibility to society, which is coordinated through the means of a democratic government.

Stephane Dion ran for the leadership of the Liberal party in 2006 on a message of Canadian unity and adding environmental responsibility to the social and economic basis of the party’s values, creating what he called the “three-pillars approach”, and while I had already been a member of the party and a small-time volunteer in elections for more than 10 years by that point, Dion’s arrival and message motivated me to throw myself into it, and I volunteered on his campaign, writing a semi-automated media monitoring tool for his team that tracked around 1000 political blogs, which, in the time before facebook took off or twitter had been invented, were the main way private citizens participated in what we would today call the social media environment.

For me, Dion’s environmental message was as important as his unity message, and I wanted to be a part of a movement that took climate change on as the defining issue of our time.

In December of 2006, Dion won the leadership on the 4th ballot at the convention in Montreal, and I stayed involved in the party very actively over the next 13 years.

For me, the Liberal party was the vehicle by which I could best participate to keep Canada united and get us to work on the existential climate crisis we face today. Change is easier to achieve from inside than it is from outside, as long as you don’t lose focus on why you got yourself inside in the first place.

Three years after Dion became leader, I got my first job as a political staffer, working for Liberal MP Frank Valeriote in his Guelph, Ontario constituency office from summer 2009 until summer 2010, when I moved to Ottawa with the intention of finding work as a political staffer on the Hill.

By 2012, I had worked for four MPs and had my hands in database, media monitoring, policy work, and everything you could ever dream of on the Hill and I began working for the very capable and endlessly hilarious Newfoundland MP Scott Simms.

In 2013, I told Scott I wanted to work beside him rather than behind him, and, with his blessing and his counsel, I began my campaign to win the Liberal nomination in my home riding of Laurentides–Labelle, Quebec.

It was not a riding that had voted Liberal very often, and few people believed I could actually win either the nomination, or the subsequent election. Even the Liberal Party didn’t think I could win and offered no real assistance to me through my campaign.

And eight years ago, on October 19th, 2015, I narrowly won the election over the Bloc Quebecois, who had so strongly motivated me to join the Liberal party 20 years earlier.

From there, I got to work pushing my vision for the country onto the party I had joined over fundamental core values of unity and environmental purpose.

I was a rural MP who had been elected in a party whose strength is urban. Liberals, fundamentally, do well in urban Canada and poorly in rural Canada. The Conservatives fundamentally do well in rural Canada and poorly in urban Canada.

For those who believe that the urban-rural split is inevitable and invariable, the NDP’s support does not vary significantly between rural and urban Canada. Its support is fairly constant across the country regardless of population density or riding size. Same goes for the Green party.

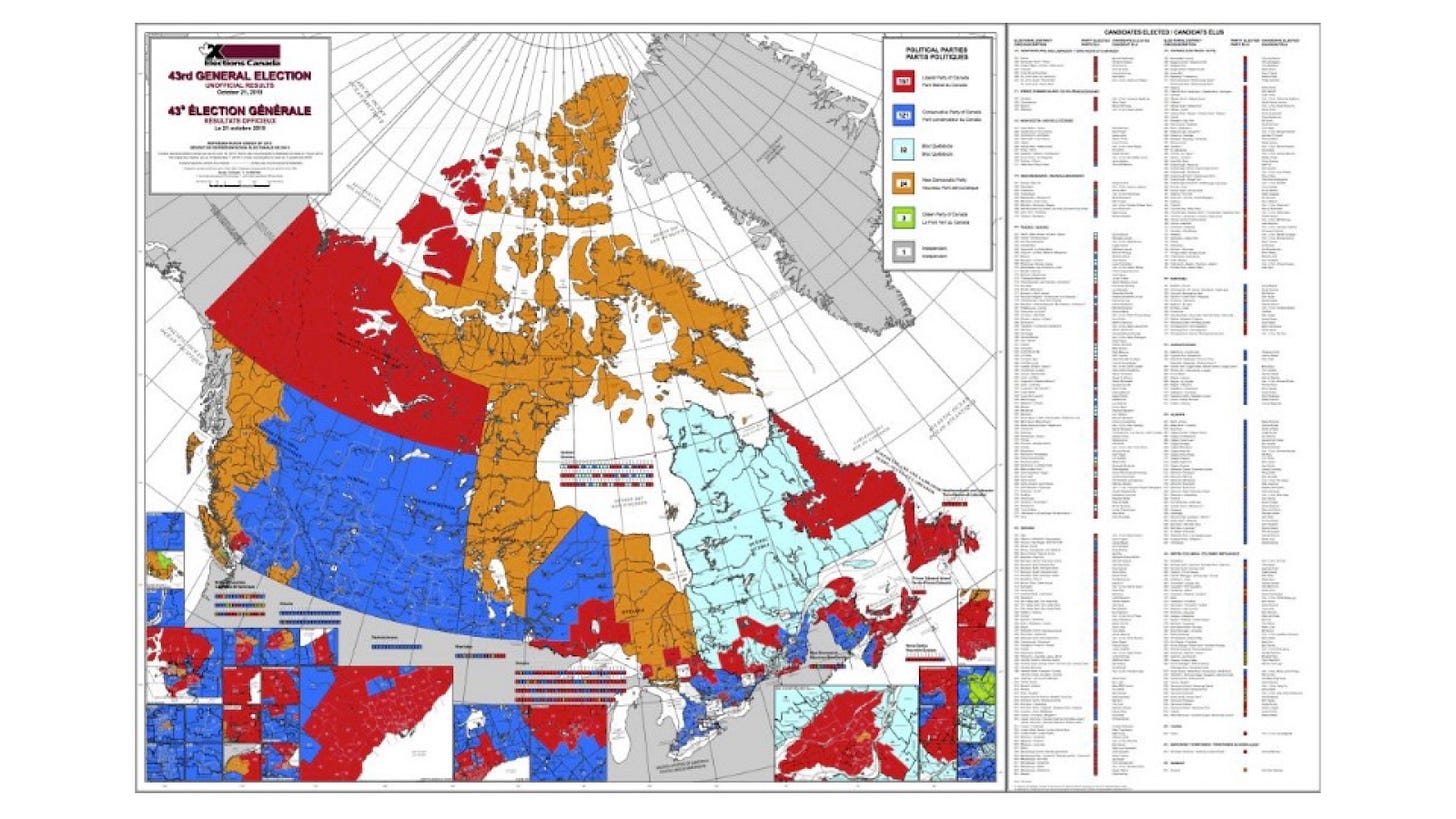

The problem we have is that, as citizens, we look at the country as a geographic map. In this view, the 2019 election was very lopsided, with the Liberals barely registering visually on the map outside of the territories.

But political parties see the map this way - in Parliament, every riding has the same weight, as demonstrated in this map of the same election.

In both cases, the way our elections actually work is totally ignored.

I was a Member of Parliament who caucused with the Liberal Party. In the election in my riding, it was my name on the ballot, not that of Justin Trudeau.

We portray our elections as a fight between political parties and political leaders, but our democracy would work a lot better if we focused on the individuals in the ridings who are the actual candidates representing actual values.

Parties, after all, are meant to be a coalition of people working together to solve common problems, not simply a sports team winning an electoral fight for the singular purpose of holding power, without a clearly defined vision of what to do with that power.

What parties are, and what parties should be, is getting further and further apart.

Note: this is the prepared text for my remarks to the University of Alberta’s first year political science course this morning prior to a lengthy planned Q&A; the version as delivered may differ from this draft. The in-person presentation also includes numerous additional slides which are not displayed here for practical reasons.

I hope it went well David! Great observations! I hope you will jump back in after a good rest...perhaps in a riding that will better appreciate all the work you put in!