The Lighter Side of Hill Work

Not everything on the Hill is serious

When I started working for him, Scott Simms was the elected chair of the Atlantic Liberal Caucus, and, as the biggest regional caucus in the emaciated 2011 National Liberal Caucus, they met in the same room as the full National Caucus. As we were no longer government or official opposition, the meetings took place in the Aboriginal room, a Senate-controlled meeting room at 160-S Centre Block. At the time, Senate Liberals made up more than half of the National Liberal Caucus.

Continued from Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 ]

At one of the first meetings I attended as assistant to the Chair, we found a wooden box on the table in front of the seat assigned to the meeting Chair. Looking for a gavel for him to use, I pressed the red button on the front of the box that looked like a latch release. It did not pop back out, appearing to be jammed, and Scott and Senator George Baker, who had been the MP in Scott’s riding before Scott, took the box and joined me in trying to figure out how to get it open.

A moment later, the box firmly in Baker’s hands, two Senate security officers ran in, evaluated the room, laughed, and radioed something to the effect of “false alarm, it’s just Senator Baker again.” There was, alas, no gavel to be found in the portable panic button.

Working for Scott was endlessly entertaining. While actually profoundly intellectual, you would never know it meeting him. Scott lived up being a Newfoundlander to the fullest, saw the humour in everything, and put everyone around him at ease, and, provided my work got done, he was very tolerant of my antics.

On one occasion early on, Scott observed that he needed a valet – a small hanger-shaped coat rack that holds a single coat. I looked it up and discovered that, for what you would get, they were quite expensive. So a few days later, I brought in a surplus 6 foot shelving bracket, some dollar store string, a couple of elastic bands, a hanger, two thin strips of ¾” plywood that I had left over from a shelving project in my apartment, and a handful of screws and a screwdriver. I bent the shelving bracket into an inverted question mark, screwed the two half-inch wide pieces of plywood to it as feet, used the string as guy wires to stabilise the structure, then I attached the hanger with the elastic bands to the top of the bracket.

The result? A roughly $3, if horrendously ugly, valet. Years later, Scott’s girlfriend would buy him a proper one and was disappointed when he refused to get rid of the one I had made him, which, more than a decade later, he still has.

The previous year, former defence Minister Peter MacKay had made national headlines when it was revealed that he had been reeled into a Cormorant rescue helicopter from a fishing trip in Scott's riding, whisked off to make a government announcement. In practice, any excuse to provide training and rehearsal to search and rescue personnel should be taken, but the “optics”, that soul-crushing focus of all things in politics, were poor.

When I joined the office in 2012, I noticed that Scott had a good quality metal model Cormorant rescue helicopter on the top shelf of the bookcase behind his desk. I observed to Scott in the autumn that his helicopter needed to fly.

My parents came to visit me in Ottawa in December and I told them of my plans. We discussed how to make it work and early that Friday morning my parents went to the hardware store to pick up some materials while I went to the office to start my day. They arrived about an hour later and we got to work.

We ran a fishing line between electrical conduits at each end of the office near the ceiling. I made a bracing system out of more fishing line for the helicopter to keep it suspended in apparent level flight and used a short metal cable with a loop at each end to permanently affix the helicopter about six inches below the fishing line, and hung a second such cable from the winch mount on the side of the helicopter.

Under the winch cable, I attached a photo of Peter MacKay, and the helicopter and its dangling passenger could be freely lobbed across the ceiling the length of the office along the fishing line for the duration of our tenure together in the suite.

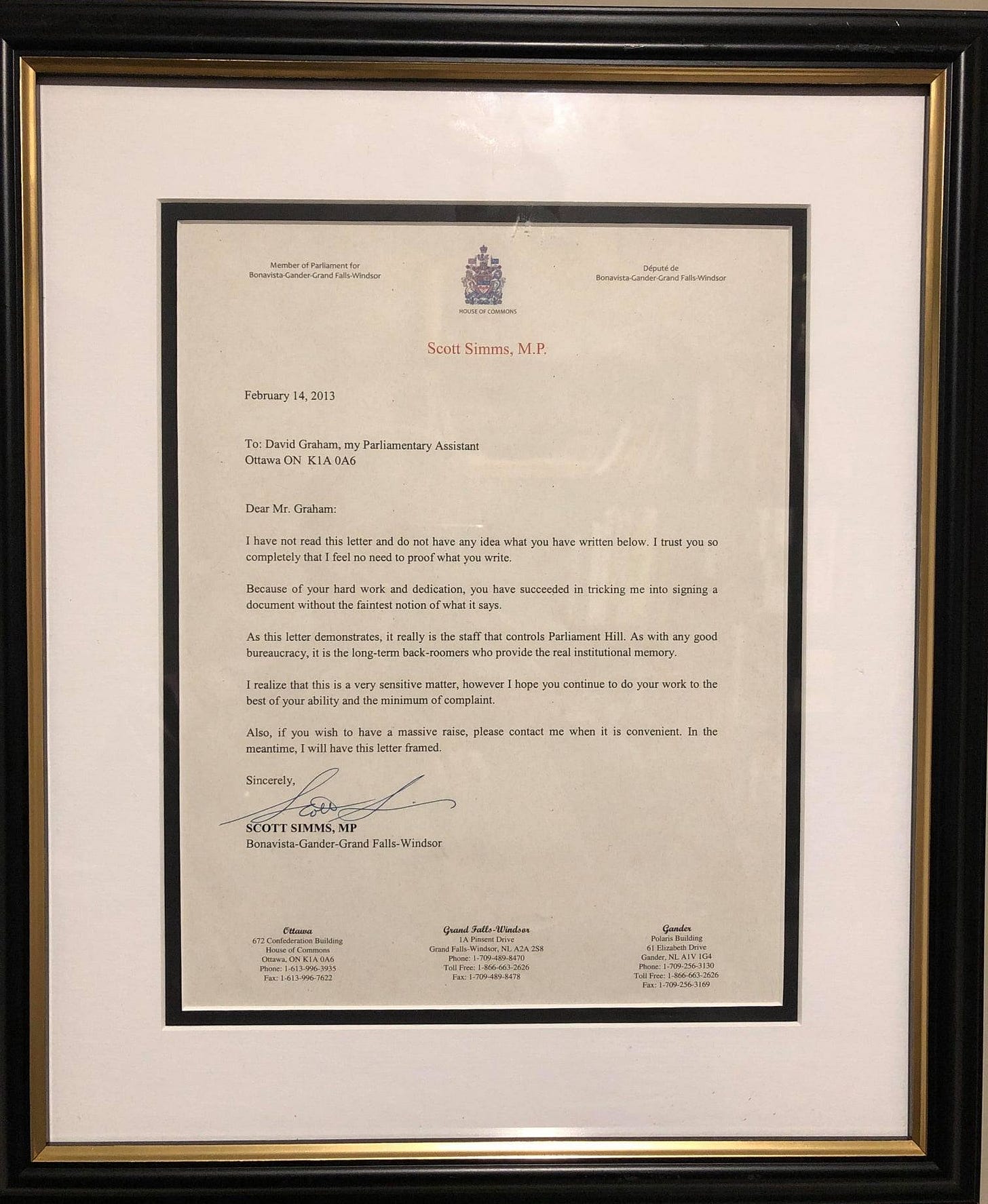

A few weeks later, on February 12, 2013, I handed Scott a pile of letters to sign. He signed them and gave them back to me. I observed that he hadn't read them, and said to him: "If I give you a letter that reads 'I have not read this letter', would you sign it?"

"Of course not!" he told me, and, when pressed: "if you ever pull it off, I'll have it framed!"

Always up for a challenge, two days later I stuck a letter in a stack of letters to sign waxing eloquently about how the signer had not read it, trusted his staff fully, would be offering a raise, and would have this letter framed. After getting the now-signed letters back a few minutes later, I stuck a note on that letter and returned it to him with a victorious grin and was greeted with something of a scowl – and admission of defeat.

I brought the letter to the Parliament Hill framing shop at the Promenade building, later renamed Valour building by Harper’s government’s obsession with everything military that did not involve actually helping veterans, but did not have the delegated authority required to authorise the expense required to perform the framing. I pointed out that the letter clearly stated that it would be framed and had been clearly signed by the Member. Unable to refuse the request, it was framed and ultimately placed over his desk, remaining there two and a half years later when his desk became mine.

To the best of my knowledge, none of my staff ever pulled off the same stunt…

Scott’s style as a boss was that of a leader, not of a dictator. One day in the spring of 2013 I made a goofy mistake that caused him some embarrassment when I put an event on his calendar for one day after it happened. The event was hosted by his long-time friend Charles King, who had been suffering from cancer, and Scott had shown up the next day vainly trying to get in the locked door of the venue.

The following morning, he came into the office and asked me to open his calendar and look at the event. In the detail notes, it clearly had the correct date information, and I had simply put it in the wrong place. He asked me to please call Charles King and apologise to him. Charles, a popular figure on the Hill, was very gracious, laughing as he visualised Scott trying desperately to enter the site on the wrong day.

A few days later, I visited the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa and discovered a remote-controlled Labrador rescue helicopter in the gift shop. I brought it into the office and flew it around the Cormorant, landing it on Scott’s desk in front of my uncharacteristically somber boss.

It cheered Scott up; I didn’t know it yet, but Charles King had passed away that morning.

Simms was quite a character. Nice to see you could have a little fun with him!